Title image above is copyright © Optimate Group Pty Ltd

(This article was originally published 20th June 2019 here on our Australian Botanical Art site.)

First published here 6th February 2021

You may have noticed that we’ve listed all our flowers by their common names as well as their scientific names, and you can even search by either with the search bar at the top of every page.

While some plants have several common names (eg ‘Hardenbergia’, ‘Native Sarsaparilla’ and ‘Purple Coral Pea’ are all the same plant), all plants (and animals, and fungi, etc) have one and only one scientific name.

Scientific names are used by scientists to ensure no ambiguity when speaking or writing to each other. A botanist referring to Hardenbergia violacea is understood by every other botanist on the planet to mean this plant. If they were to refer to ‘Native Sarsaparilla’ however, did they mean this plant (Smilax glyciphylla) or this plant (Hardenbergia violacea)?

And what if they were speaking to botanists in other countries? Maybe they have their own version of ‘Native Sarsaparilla’ there — like this Mexican/Central American plant!

Another name for ‘scientific name’ is binomial nomenclature.

Binomial nomenclature was devised by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 as a formal system for naming species. Each species has a two-word name: the first word describes the genus it belongs to, and the second word is its species name. A genus may have within it several species, but each species name is unique. There is only one of each species, ever.

For example, we have several Eucalyptus species available as prints. Each of these has characteristics that botanists agree place them in the Eucalyptus genus and not, say Corymbia.

Yet each has its own unique species name: Eucalyptus sideroxylon has enough in common with Eucalyptus leucoxylon for them both to be Eucalyptus, but E. sideroxylon is different enough to E. leucoxylon to warrant each a separate species. (The genus can be abbreviated to its capital letter and a full stop as done here, but only when there is absolutely no confusion as to which genus is meant.)

(And there is enough variety within the E. leucoxylon species to justify separate subspecies!)

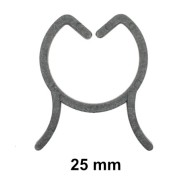

Use of binomial nomenclature comes with very strict rules. Both the genus and species name must always be italicised (or, if handwritten, underlined). The genus is always capitalised and the species is always lowercase. There are no exceptions to this.

Groups of species belong to genera (plural of ‘genus’), and groups of genera belong to families (and there are higher classification groups again) but it is only the genus and species which are italicised.

If a plant is known to be a eucalypt, but its species is unknown or doesn’t need to be known, it would be referred to as Eucalyptus sp. (abbreviation for ‘species’, and note the full stop).

Several eucalypts similarly unknown or not needed to be known would be written Eucalyptus spp. (the plural form).

The abbreviation for ‘subspecies’ is ‘subsp.’ in botany.

‘sp.’, ‘spp.’ and ‘subsp.’ are not italicised.

Many plants are popular with gardeners, and ‘cultivars’ (‘cultivated varieties’) have been developed within some species. The cultivar name is appended after the common or binomial name, and written without italics and between single quotation marks, eg Eucalyptus sideroxylon ‘Rosea’.

Some common garden plants are hybrids of two species, and these are written as the genus with the cultivar appended, and often with the species that were crossed as well.

Examples are Anigozanthos ‘Yellow Gem’ (Anigozanthos flavidus × Anigozanthos pulcherrimus) and Grevillea ‘Robyn Gordon’ (Grevillea banksii × Grevillea bipinnatifida).

Leave a Comment