Title image above is copyright © Kristi Ellinopoullos

(This article was originally published 18th August 2020 here on our Jujube Tree Nursery site.)

First published here 19th January 2025.

Microbes Generally

‘Microbes’ means ‘germs’ to most people, and yet maybe one in a billion microbial species is a human pathogen. ‘Only’ 1,400 or so species have been described as a human pathogen, and this number includes the non-microbial parasitic worms as well as the microbial viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Other species are of course pathogenic to other animals and plants, but again the total number is minuscule compared to the many, many others that are beneficial at best and completely harmless at worst.

The total number of all microbes on Earth is a staggering concept to comprehend, and this article cites some incredible numbers. There are 1031 viruses alone — that’s a 1 with 31 zeros after it! There are 100 million times more bacteria in the oceans than there are stars in the known universe. Our gut bacteria weigh a kilogram, a gram of dental plaque (!) contains 1011 bacteria, and apparently we excrete our own bodyweight in faecal bacteria each year.

(I do recommend you read the article yourself for other fascinating tidbits — be blown away at just how toxic the botulinum produced by Clostridium botulinum is!)

And in soil? Just one teaspoon of soil contains about a billion microbes, belonging to a microbiome.

What is a Microbiome?

A microbiome is a community of microorganisms in a particular environment. The human gut microbiome is one getting a lot of attention these days, but there are many others less well-known. The microbes on our skin are one. Ruminants have their unique microbiomes internally and externally, as do other animals and plants. Rivers, oceans and lakes have microbiomes, as do thermal springs and mud volcanoes.

And of course soils are no exception.

The Soil Microbiome

In reality there are many different soil microbiomes, each adapted to the many different soils across the globe. A soil’s composition, moisture content, pH, organic matter content, salinity, degree of oxygenation, and temperature range will all shape the microbial community it supports.

Even the driest, saltiest sand devoid of organic matter and plant life will have some microbial life. Some bacterial species literally make their own food via the inorganic minerals in soils — these chemolithotrophs ('nourishment from rock chemicals') oxidise iron-, nitrogen- and sulfur-containing minerals and channel the electrons obtained into a pathway that ultimately converts carbon dioxide into glucose.

The richer soils that can and do support plant life have a more complex microbiome that has been brought about by the plants themselves — the root, or rhizosphere microbiome.

The Rhizosphere (Root) Microbiome

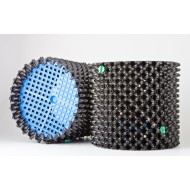

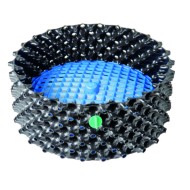

The rhizosphere microbiome occupies a narrow 1–2 mm region around each and every root of a plant. A mutually beneficial relationship develops here between the microbes and roots, in which each helps feed the other. The roots secrete carbon-rich food sources which attract microbes, and in return microbes make other substances more plant-available to the roots. Bacterial species fix nitrogen and make available other macro- and micronutrients such as sulfur, iron, manganese, copper and zinc. Mycorrhizae (plural form of mycorrhiza, ‘root fungus’) extend a plant’s roots by sending out long hyphae which bring back water, phosphorus, and nutrients in return for carbohydrates.

There is so much more to feeding a plant than giving it fertilisers and water — it also needs a healthy, thriving rhizosphere microbiome for maximum health, and this is a topic I very much intend to go deeper into!

Leave a Comment